What Florence Nightingale Can Teach Us About Modern Workplace Design

Key Points

Health & wellbeing are shaped by the environment. Florence Nightingale recognised, long before research confirmed it, that the spaces we inhabit shape physical health and psychological wellbeing - a truth now central to modern evidence-based design.

Healthy buildings deliver real results. The WELL Building Standard is helping organisations translate research into measurable people and business outcomes - from better focus and mental health to higher job satisfaction and retention.

High-risk workplaces need a trauma-informed lens. In settings where staff are regularly exposed to trauma or distress, trauma-informed design plays a critical role in addressing psychosocial risks for both staff and clients.

The Wisdom of Florence Nightingale

For all our progress in medicine, technology, and architecture, is it possible we’ve lost touch with early wisdom about what truly keeps us well?

Long before science proved that light governs our circadian rhythm or that views of nature can reduce pain, Florence Nightingale - a 19th-century nurse and public health reformer who linked the environment to recovery - wrote about the healing power of design:

“The effect in sickness of beautiful objects, of variety of objects, and especially of brilliancy of colour, is hardly at all appreciated… People say the effect is only on the mind. It is no such thing. The effect is on the body, too. Variety of form and brilliancy of colour in the objects presented to patients are actual means of recovery.” [1]

Nightingale observed what modern science now confirms: the body responds directly to its surroundings. Light, sound, temperature, and materials can either restore balance or deplete it.

In our rush toward efficiency, we’ve made buildings smarter, faster, and more functional - but not always healthier. We’ve created environments intended to drive productivity, yet they quietly erode the biological systems that sustain performance.

As we face rising rates of burnout and mental illness, it’s worth reflecting on Nightingale’s enduring wisdom - that the body doesn’t function in isolation. Human health is directly supported or undermined by our surroundings.

From Building Standards to Human Standards

While modern science confirms what Nightingale came to understand through observation, frameworks like the WELL Building Standard are leading a global shift toward treating buildings, and workplaces in particular, as active ingredients in supporting human health and wellbeing.

At the WELL Building Summit held in Sydney in August, this idea took centre stage. The WELL Standard translates the growing body of research on healthy environments into measurable design strategies that address characteristics such as air quality, light, movement, sound, thermal comfort and materials.

Research from the International WELL Building Institute shows that workplaces designed to the WELL Building Standard deliver measurable improvements in health and wellbeing [2].

WELL-certified workplaces are reporting significant returns on investment with financial benefits stemming from improvements in productivity, lower absenteeism and increased job satisfaction and retention [3].

Yet amid these advances, we have some way to go in creating truly supportive workplaces. At the Summit, Professor Christhina Candido from the University of Melbourne, pointed out that while improvements overall are being seen in visual comfort, air quality and thermal comfort, acoustic comfort continues to decline.

Noise remains one of the most significant and under-addressed issues in workplace design. I would hazard a guess that this is related to the ongoing push for more economical - and supposedly collaborative - open-plan offices, and a lack of alternative options for focused work and reprieve.

We’d do well to heed Nightingale’s warning that:

“unnecessary noise is the most cruel absence of care that can be inflicted on the sick or the well.” [1]

Studies show that excessive noise leads to stress, daytime sleepiness, reduced cognitive performance, high blood pressure and even an increase in the incidence of cardiovascular disease [4]. For people already working in emotionally demanding roles, poor acoustics compound the cognitive and psychological load.

While standards like WELL are pushing us toward a new focus on health and wellbeing in architecture and design, they are not enough in high-risk workplaces where staff are exposed not only to common issues such as noise, but also to trauma.

These settings demand an additional lens: one that recognises the invisible environmental stressors that contribute to increased psychosocial risk.

Why High-Risk Workplaces Need a Trauma-Informed Design Lens

In workplaces where staff support those in crisis such as addiction recovery, domestic-violence, ill health or homelessness, exposure to distress, aggression and trauma is routine. While the WELL Standard provides a valuable foundation for supporting general physical health and wellbeing, I believe that it doesn’t yet address the emotional terrain of this work.

Nonetheless, these realities are increasingly reflected in policy and regulation, which now recognise psychological harm as a workplace health and safety issue.

Australia’s Work Health and Safety (WHS) Regulations now make this explicit. Employers are legally required to identify and manage psychosocial hazards - aspects of work and the workspace that may cause psychological harm, including chronic stress, exposure to trauma, and environmental strain [5].

Factors such as noise, lack of privacy, or constant unpredictability can increase mental and emotional fatigue, creating psychosocial hazards for staff. These factors can no longer be considered issues of preference or comfort; they are matters of compliance, care, and ethical responsibility.

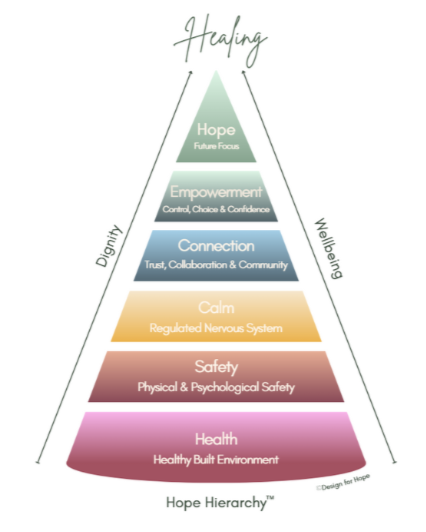

A trauma-informed design lens, such as the Hope Hierarchy™, builds on frameworks like WELL by focusing on the psychological impact of high-risk workspaces.

Health as the Bedrock of Recovery, Resilience and Hope

These ideas come together in the first layer of the Hope Hierarchy™ - Health - which provides the foundation for all other psychological processes underpinning recovery, resilience and hope. Health is the starting point because it anchors the body and the mind’s capacity to regulate, rest, and restore. Health is a necessary precondition for building psychological safety, social connection and empowerment.

High-risk workplaces designed to support both client and staff wellbeing go beyond current healthy building standards to address psychosocial risk factors through trauma-informed design. In these settings, design functions as an active agent in recovery and resilience - shaping sensory experience, emotional regulation, and the quality of care provided.

Florence Nightingale understood that the physical environment was key to health and wellbeing. She saw beauty, light, and colour as “means of recovery”. Modern science now confirms her observations, showing us that health is shaped not only by biology but by our surroundings.

When we design for health in this deeper sense, we’re not only protecting the body but also creating the conditions for recovery, resilience, and ultimately, hope.

Final thoughts

In the context of today’s workplaces, designing for health isn’t just good practice - it’s a strategic and regulatory imperative that nurtures and sustains both clients and staff.

More than 160 years ago, Florence Nightingale observed that restoring health and wellbeing begins with the environment - that light, beauty, and colour are not luxuries, but instruments of healing. Her insights remain profoundly relevant to modern workplace design, especially in high-risk settings.

When those same principles guide the design of our workplaces, we create environments that sustain performance, protect wellbeing, and embody what Nightingale understood so clearly - that health and wellbeing are shaped by place.

If you’d like to start a conversation about how to create a workspace that truly supports the wellbeing of your staff, book a call with me.

References

Nightingale, F. (1860). Notes on Nursing: What It Is, and What It Is Not. Harrison and Sons.

International WELL Building Institute (IWBI). (2023). The WELL Building Standard, v2: Improving Health and Wellbeing through Building Design. New York, NY.

International WELL Building Institute (IWBI). (2025). Investing in health pays back: The business case for healthy buildings and healthy organizations. New York, NY.

Basner, M., Babisch, W., Davis, A., Brink, M., Clark, C., Janssen, S., & Stansfeld, S. (2014). Auditory and non-auditory effects of noise on health. The Lancet, 383(9925), 1325–1332.

Safe Work Australia. (2024). Model Work Health and Safety Regulations Canberra, ACT. https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/