Rethinking Hope

The role of hope in creating optimal environments for trauma recovery

Key Points

Hope isn’t a soft concept, it’s a science-backed catalyst for recovery. Studies consistently show that hope improves health outcomes and psychological wellbeing for people facing trauma, illness, addiction, and violence.

To foster hope, the physical environment must signal safety, calm and possibility. Yet in many recovery environments, institutional, chaotic, or poorly designed spaces can undermine the healing process.

Trauma-informed design (TID) offers a powerful opportunity to align physical spaces with psychological needs. And at the centre of that opportunity is hope.

What Is Hope?

Is hope just wishful thinking or naïve optimism?

Perhaps you’ve heard hope dismissed as a “soft concept” or a luxury in the face of real-world problems, especially recovery from trauma.

But what if hope was critical to healing?

When we examine the science, we discover that hope is neither vague nor expendable in the recovery process. What we know from research is that hope is measurable, malleable and predictive of the life outcomes of trauma survivors.

In psychological science, hope is recognised not merely as an emotion, but as the capacity to envision meaningful goals, believe that they can be achieved, and stay motivated to work towards them despite setbacks [1]. Hope is active, not passive. And it’s not just a theoretical concept – the experience of feeling hopeful activates areas of the brain responsible for planning and working towards your goals [2].

Importantly, hope is learnable. It can be strengthened through targeted interventions, making it a powerful, practical tool in trauma recovery [3].

Hope Drives Recovery

Across a wide range of populations and conditions, higher levels of hope are linked with better health and psychological outcomes.

Physical Illness: Hope improves quality of life, immune function, pain levels, symptom management and even long-term prognosis for people living with cancer and chronic disease [4-7].

Addiction: Among those recovering from opioid dependence, increased hope reduced the risk of relapse by 23% after completing a detox program [8]. Hope is also linked with improved emotional regulation and better adherence to addiction treatment plans [9].

Domestic Violence: Higher levels of hope can improve self-worth and lower the risk of depression and suicidal ideation for victims of domestic violence [10].

Mental Illness: Hope-based therapies can lead to significant improvements in resilience, self-care behaviours and overall wellbeing for people experiencing depression [11].

Older Adults: Being more hopeful is linked to fewer chronic conditions, reduced pain, healthier behaviours, and even lower mortality rates for older adults [12].

It’s clear that hope is not a luxury but a powerful tool for improving recovery outcomes.

The Problem: Trauma Disrupts Hope

And yet, trauma can block access to hope. It alters how people see themselves, their futures, and their sense of control. The people who need hope the most, find it hardest to draw on this inner resource for healing.

The challenge for trauma recovery services is clear: given the importance of hope in recovery, how can we intentionally build hope for people who may struggle to access it?

The Missing Piece: Design as a Catalyst

As hope emerges as a key driver of trauma recovery, organisations dedicated to healing are adopting hope-based therapeutic interventions to enhance their clients’ life outcomes. Yet, too often, the environments in which people seek support are sterile, institutional, chaotic or even retraumatising.

The physical environment is not neutral. It can either undermine or support the emergence of hope and recovery from trauma. This is where Trauma-Informed Design (TID) plays a vital role.

While the ethos of TID is gaining traction, its application remains inconsistent and is often based on good intentions rather than science, leading to environments that may fall short of truly supporting recovery. This has tangible implications for those seeking healing. Without a standardised, evidence-based approach, there is a risk of creating spaces that inadvertently retraumatise or fail to foster hope.

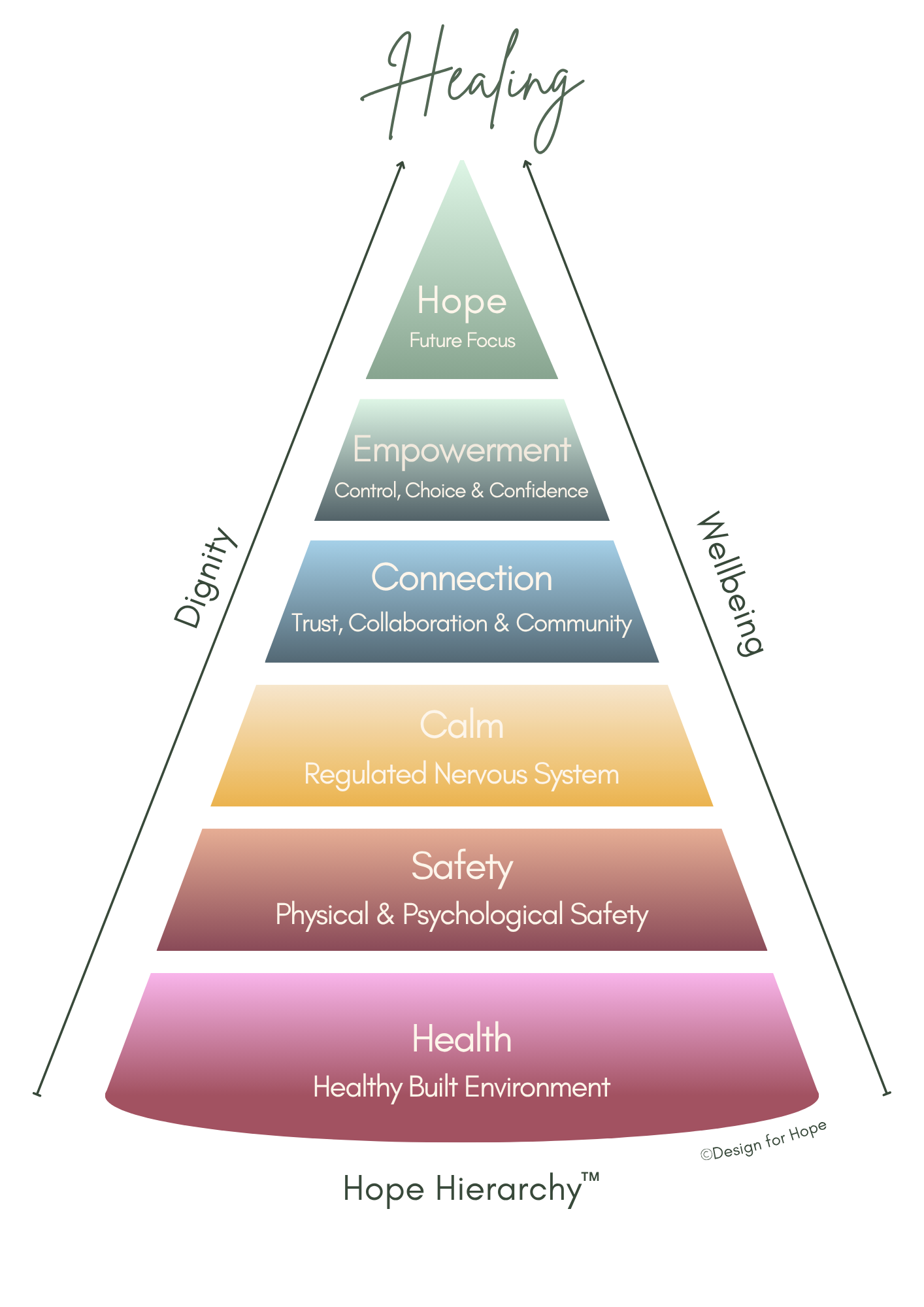

Introducing the Hope Hierarchy™

To meet this need, I developed the Hope Hierarchy™, a trauma-informed framework that translates science into actionable design strategies that genuinely support wellbeing and recovery.

It consists of six levels, each facilitating a distinct stage of trauma recovery, from stabilisation to personal agency and, ultimately, hope. The Hope Hierarchy™ guides and empowers organisations to create the environmental conditions in which hope can emerge, take root and grow.

1. Health: Laying the Foundation for Healing

Trauma often leaves survivors with compromised health and heightened physiological stress. Poor environmental conditions such low air quality, noise or mould can prolong stress responses and undermine healing [13].

Designing for health means creating environments that support core biological functions. The WELL Building Standard, for example, emphasises the importance of air, light, noise, and thermal comfort for supporting physical wellbeing.

Physical health is the bedrock of the Hope Hierarchy™. If a space doesn’t support health, it can’t support hope.

2. Safety: Finding Solid Ground

Trauma disrupts the brain’s ability to distinguish real danger from perceived threat. As a result, survivors often remain in fight-or-flight long after the danger has passed. This can result in emotional dysregulation, chronic exhaustion, social isolation, and a reduced capacity to engage with support services.

And it’s not enough for a space to be safe; it must also feel safe. A locked door might offer security, but if the environment feels unpredictable or hostile, it is psychologically unsafe.

A recent study involving residents in permanent supportive housing, found that those who perceived their housing as safe and of good quality showed fewer trauma related behaviours compared to those who viewed their environment as unsafe or poor in quality [14].

3. Calm: Quietening the Nervous System

Studies show that trauma impacts the nervous system, frequently causing emotional dysregulation and oversensitivity to sensory input including noise, movement and light. The physical environment plays a key role in regulating the nervous system to improve mental health and support long-term recovery [15].

Design strategies that reduce environmental chaos, remove trauma triggers and bring a sense of calm can help shift the body and brain from a state of high alert (fight or flight) into one of rest and recovery. For example, biophilic design, which involves bring natural elements into interior spaces, has been consistently linked to lower blood pressure, decreased stress hormones and reduced aggression [16].

4. Connection: Feeling Seen and Respected

Humans are wired for connection, but trauma can erode trust in others, disrupt relationships, and diminish a sense of identity. Survivors may struggle with isolation and social withdrawal, symptoms that are often reinforced when environments feel institutional or alienating.

The physical environment plays a critical role in restoring connection - not just with people, but with culture, community, and self.

People need to feel seen and respected in a space to feel safe enough to connect with others. Studies show that environments that reflect cultural identity and offer privacy, foster a sense of belonging and connection and increase the likelihood of someone sticking with a recovery program [17-18]. Trust and connection are rebuilt when dignity is upheld by design.

5. Empowerment: Rebuilding Agency and Identity

A common consequence of trauma is the loss of agency and personal identity. For survivors of trauma, whose lives have often been shaped by a sense of powerlessness, having the ability to control their surroundings can be profoundly reparative.

Research shows that coping self-efficacy, or a sense of empowerment, is a strong predictor of symptom reduction in PTSD treatment [19]. Design can foster agency and ownership of the healing journey by offering meaning choices such as the opportunity to personalise one’s space, adjust lighting, and securely store personal belongings.

As psychologist Albert Bandura explains, when you believe that your actions can make a difference in your life, you become more resilient and motivated to make the necessary change [2o]. Even small acts of design participation can help build the confidence to try and a renewed sense of self.

6. Hope: Reclaiming the Future

Hope is the final level of the hierarchy, not because it is optional, but because it can’t emerge without the biological and psychological foundations laid by the others.

When a space symbolises forward movement, growth and transformation, it can help survivors imagine a better future. This is the essence of hope - not forced positivity, but a credible sense that healing is possible, worth pursuing, and within reach.

A trauma-informed space provides non-verbal cues of progress and possibility. When someone enters a room and feels emotionally lifted, they are responding to more than visual aesthetics, they are experiencing hope in embodied form.

Final Thoughts: Hope Is Strategic

Hope is often dismissed as a soft or optional concept. But in trauma recovery, hope is both a predictor and a pathway to better outcomes. It is measurable, learnable, and deeply influenced by the physical environment.

When organisations align their physical spaces with the psychological journey of recovery, they don’t just provide a place to heal - they create the conditions for healing to occur.

The Hope Hierarchy™ offers an evidence-based roadmap to create healing spaces with rigour and clarity. Through trauma-informed design, we can move beyond safety to something deeper: the rebuilding of dignity, wellbeing, and hope.

Because recovery is not just about surviving the past. It’s about believing in the future.

Curious about how trauma-informed design can transform your space? Schedule a free call or email us directly.

Design for Hope partners with business leaders responsible for the health and wellbeing of their clients and staff to create environments where change isn't just possible - it's tangible, intentional and transformative.

References

Snyder, C. R. (2002). Hope Theory: Rainbows in the Mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13(4), 249–275.

Xiang, G., Li, Q., Xiao, M., He, L., Chen, X., Du, X., Liu, X., Song, S., Wu, Y., & Chen, H. (2021). Goal setting and attaining: Neural correlates of positive coping style and hope. Psychophysiology, 58(10).

Pretorius, C., Venter, C., Temane, M., & Wissing, M. P. (2008). The design and evaluation of a hope enhancement programme for adults. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 18(2), 301–308.

Vellone, E., Rega, M. L., Galletti, C., & Cohen, M. Z. (2006). Hope and related variables in Italian cancer patients. Cancer Nursing, 29(5), 356–366.

Lundquist, D., Durbin, S. M., Pelletier, A. J., Petrillo, L. A., Bame, V., Turbini, V., Heldreth, H., Lynch, K., McIntyre, C., Juric, D., Ferrell, B., Jimenez, R. B., & Nipp, R. (2023). Patient-reported hope, prognostic understanding, quality of life, symptom burden, coping mechanisms, and financial wellbeing in early phase clinical trial participants. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 41(16_suppl), 12109.

Faller, H., Bülzebruck, H., Schilling, S., Drings, P., & Lang, H. (1997). Do psychological factors modify survival of cancer patients? II: Results of an empirical study with bronchial carcinoma patients. Psychotherapie Psychosomatik Medizinische Psychologie, 47(6), 206.

Lutgendorf, S. K., Whitney, B., Thaker, P. H., Penedo, F. J., Noble, A. E., Cole, S. W., Sood, A. K., & Corn, B. W. (2023). The biology of hope: Inflammatory and neuroendocrine profiles in ovarian cancer patients. Brain Behavior and Immunity, 116, 362-369.

Reddon, H., & Ivers, J. H. (2022). Increased levels of hope are associated with slower rates of relapse following detoxification among people living with opioid dependence. Addiction Research & Theory, 31(2), 148–154.

Mathis, G. M., Ferrari, J. R., Groh, D. R., & Jason, L. A. (2009). Hope and Substance Abuse Recovery: The Impact of Agency and Pathways within an Abstinent Communal-Living Setting. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery, 4, 42–50.

Muyan, M., & Chang, E. C. (2019). Hope as a Mediator of the Link Between Intimate Partner Violence and Suicidal Risk in Turkish Women: Further Evidence for the Role of Hope Agency. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34, 4620–4637.

Wang, X., Song, H., & Zhang, S. (2025). Nursing interventions based on Snyder’s hope theory for depression following percutaneous coronary interventions: A clinical study. World Journal of Psychiatry, 15(2).

Long, K. N. G., Kim, E. S., Chen, Y., Wilson, M. F., Worthington, E. L., Worthington, E. L., & VanderWeele, T. J. (2020). The role of Hope in subsequent health and well-being for older adults: An outcome-wide longitudinal approach. Global Epidemiology 2, 100018.

Evans, G. W., & Kantrowitz, E. (2002). Socioeconomic status and health: The potential role of environmental risk exposure. Annual Review of Public Health, 23(1), 303–331.

Hawes, M. R., Chakravarty, D., Xia, F., Max, W., Kushel, M., & Vijayaraghavan, M. (2024). The Built Environment, PTSD Symptoms, and Tobacco Use among Permanent Supportive Housing Residents. Journal of Community Health, 50(2):369-376

Rasoulpour, H., & Charehjoo, F. (2017). The Effect of the Built Environment on the Human Psyche Promote Relaxation. Architecture Research, 7(1), 16–23.

Ulrich, R. S. (2008). Biophilic theory and research for healthcare design. In S. Kellert, J. Heerwagen, & M. Mador (Eds.), Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life (pp. 87–106). Wiley.

Ajeen, R. et al. (2023). The Impact of Trauma-Informed Design on Psychological Wellbeing in Homeless Shelters. Psychological Services, 20(3), 680–689.

Pable, J. (2012). The Homeless Shelter Experience: Influence of Physical Environment on Resident Outcomes. Journal of Interior Design, 37(3), 9–23.

Murphy, J. W., Shotwell-Tabke, C., Smith, D. L., Valdespino‐Hayden, Z., Patton, E., Pridgen, S., & Held, P. (2025). Evaluating self-efficacy as a treatment mechanism during an intensive treatment program for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. Freeman.